Cognitive Bypassing of Cognitive Behavior in Product Design

I’m not a big fan of everyday products becoming art projects to then become better products.

Perhaps, I should start by defining an “everyday product’ first.

An everyday product/object are the type of object that you learn the name of when you are learning a new language - like in a textbook or flashcard.

These cards are often called “picture cards.”

Common objects. Normal objects. Everyday objects.

The stuff that is not negotiable.

Things that look and do the same thing for everyone, in any language.

Chairs are chairs, toothbrushes are toothbrushes, etc…

Things that either work or don’t. And the degree of the objects workability is measurable.

There are hammers that are better at hammering than others.

An everyday object shares many of the qualities of a tool.

That is, these things don’t exist on their own. These things were created to extend our human abilities in millions of different ways.

These tools provide solutions to old problems that we’ve been solving forever - technological iteration.

Tools, and specialty tools, have a very narrow set of uses - and when they are not being used, what the heck are they supposed to do?

We store a lot of stuff that we only use for minutes a day.

Apparel and clothing are tools for keep us safe and protected from the elements.

I live in Southern California.

I have 2 “big” jackets that are almost 20 years old that I will have for the rest of my life, because I only wear them a few times a year.

This would not be the case if I lived in Minnesota.

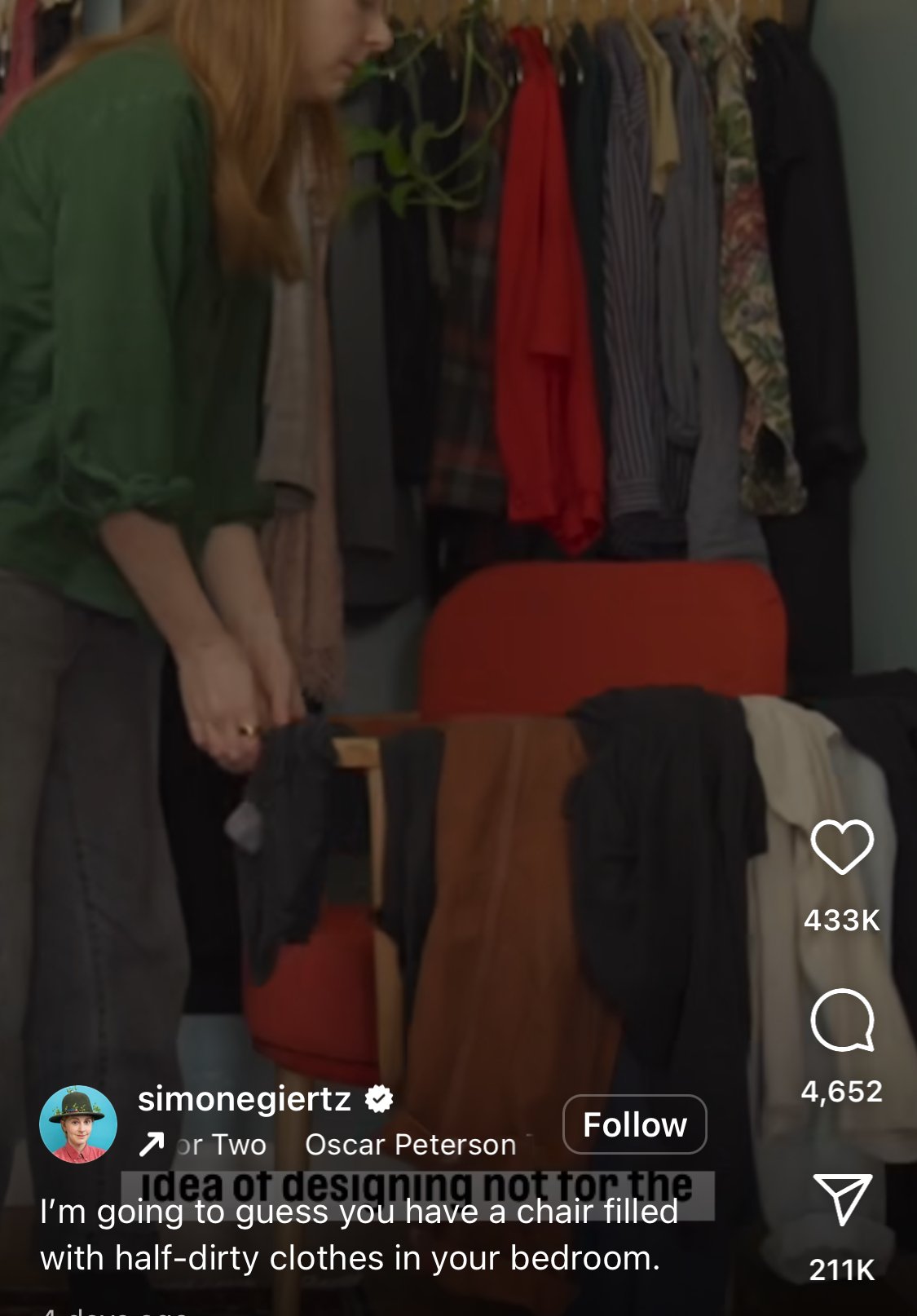

What prompted this thought train this morning, is a video of a chair that is going around on Instagram.

I’m familiar with this artist’s work, but this piece struck me as odd - but also telling.

It’s a chair, that has a swiveling component that acts as a clothes hanger.

Because - we all know what it is like to be picking out an outfit, and then we just throw the options on a chair.

The artist/designer, in this case, has made a product that solves a problem that “we all experience.”

She created a “lazy susan” mechanism with a railing - so you can drape your clothes, and rotate it around the back of the chair, so you can sit in the chair as well.

But, what is the actual problem? I’m not totally clear on that to start.

The problem is that I have a half dirty clothes in my room?

Because it seems like the problem is connected to something like - not having enough time to put clothes away in a given moment/context.

Or as the artist mentions in the video above - what do you do with all your half-dirty clothes that aren’t hamper ready, but you don’t want to put on your rack?

So it’s about space?

If we reduce it all the way down - it’s either a problem of time or space.

There is either not enough space for the thing you need to do, or not enough time.

The problem then is a “deficit of time” or a “deficit of space.”

The cardinal error, it seems, is when one misidentifies the problem one needs to solve by conflating space and time within the solution.

How does this chair create more time for the user?

It doesn’t.

And in this case, it actually takes up space, and increases another set of actions to use it.

Thus, the same amount of space being used as a normal chair, but then this new chair requires more time to use it properly.

Not to mention that the chair, cannot be used in other spaces in the house.

Well, it can, but it doesn’t look like other chairs.

Does this solve the problem, or create more of the same problem?

Does the chair/clothes rack help you make decisions about your half-dirty clothes?

Or does it just create another space to hold them, hoping you might get to them when you have time?

Do half dirty clothes become less dirty over time?

Is the overall goal to reduce wash cycles, reducing water and detergent use?

I’m struck by how often we think that the solution to our problems requires either buying more/new things, or adopting new processes, procedures, techniques, rather than just doing wayyyyyyyyy less.

I’m not a psychologist, and I’ve never read anything specific on cognitive behavioral therapy.

But! I do encounter this type of thinking with interiors often.

So I will put this into a personal anecdote to end.

If I had a client who said, “hey Eric, I’d like you to design a chair that I can hang my half dirty clothes on,”

I would respond - Why do you need a chair to hang your half dirty clothes on? You either need a chair, or a clothes rack, both of which you can get in any style, shape, color, country of origin, etc… and if you change your habits, you actually don’t need either one.

I talk myself out of a lot of potential work, but my job is to not cognitively bypass the cognitive apparatus that we engage to identify problems and solutions.

A novel problem may require a novel solution, but when that solution is a product we get novelty.

Novelty wears almost instantly.

Because novelty is privileging the emotional impact of a product, not what the product produces in your life.

If the product creates a set of procedures that are cumbersome, and don’t actually address the real problem, then the product isn’t going to relieve our mental load, it will only compound it.

Peace, love, cactus.

E